[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”94″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” qode_css_animation=””][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][vc_separator type=”normal” color=”#444444″ thickness=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][vc_column_text]At the end of March Congress passed an appropriations bill over 2,200 pages long that allocated $1.3 trillion dollars to many government programs and agencies. This massive bill also included legislation that directly impact our public lands by addressing funding for wildfires and a new categorical exclusion (CE) that allows some timber sales to move forward with less environmental review. This new CE and other policy changes in this bill are attempts to weaken our environmental laws and limit public input on our federal forests, and we must remain ready to oppose further harmful riders in future bills.

What is the appropriations bill?

A bill that is over 2,200 pages long, concerning over a trillion dollars, and written in complicated legislative language, can seem overwhelming to many of us. This large bill specifies how much money will go to different government programs and agencies for fiscal year 2018.

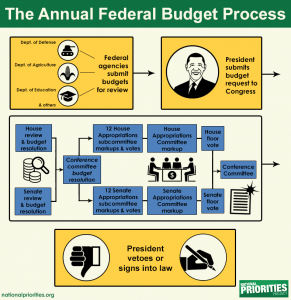

Congress is required by law to pass twelve appropriations bills allocating discretionary spending for each fiscal year, which starts on October 1. However, since Congress was unable to come to an agreement on these bills in 2017, they extended the process through March 23 through “continuing resolutions” which provide temporary funding for federal agencies and avoid a government shutdown while Congress works through the appropriations process. This spending bill is large because it is an omnibus bill that combines the twelve funding areas.

extended the process through March 23 through “continuing resolutions” which provide temporary funding for federal agencies and avoid a government shutdown while Congress works through the appropriations process. This spending bill is large because it is an omnibus bill that combines the twelve funding areas.

Appropriations bills must be passed because without them, many government agencies and programs go unfunded and must shutdown. The importance of these bills makes them a target for riders, provisions that are unrelated to federal spending but are often added onto federal spending bills. Riders are a tactic used to enact legislative changes that would be difficult to pass on their own.

How does this bill impact our public lands?

For our public lands, some of the best news comes from what is not in the bill. Thanks to the dedication of concerned citizens throughout the country, some of the worst forest management provisons were not added to the bill. Portions of the Westerman Bill, including new categorical exclusions allowing timber harvest with little environmental review, had the potential to be added to this bill as riders. Another rider would have allowed reckless logging and road-building in roadless areas in Alaska’s national forests by exempting these forests from the 2001 Roadless Rule. Exempting millions of acres of public lands in Alaska from the Roadless Rule could have set a dangerous precedent for developing roadless areas throughout the U.S.

Although several harmful environmental riders did not make it into the bill, one that did is a new categorical exclusion (CE) for hazardous fuels reduction projects up to 3,000 acres. These are projects where the agencies propose reducing wildfire risk through commercial timber harvest. New CEs for timber harvest projects are concerning because CEs limit public input and environmental review. Instead of going through the normal public input process, which involves preparing an environmental assessment and multiple public comment periods, the agencies would only have to provide public notice and one comment period. To use this CE, the Forest Service must maximize the retention of old-growth and large trees and use the best available science to maintain and restore ecological integrity. Also, these projects must be developed collaboratively, not include permanent road construction, and be located outside wilderness and other protected areas. Commercial timber harvest to reduce fuels is potentially controversial in areas with mature forest and large trees. New CEs such as this one risk cutting short public input and conversations that address these difficult topics. In our view, controversial projects necessitate a thorough public input process, where stakeholder concerns can be addressed early on, if these projects are to move forward without future challenges.

The appropriations bill also includes funding for fighting wildfires. Intense wildfire seasons over the last years have rapidly depleted the Forest Service’s budget because of “fire borrowing.” Fire borrowing occurs when the Forest Service maxes out on funds allocated for fighting wildfires and the agency uses money from other accounts. By taking money from other accounts to fight fires, the Forest Service delays other projects, including those that support recreation and restoration. The wildfire funding fix passed as part of the appropriations bill includes a cap on the Forest Service’s wildfire suppression budget and establishes a $2.25 billion emergency fund for the agency to use instead of borrowing from other programs. These changes will go into effect in fiscal year 2020, and will help the Forest Service retain funds for ecological restoration and recreation services in future years.

Secure Rural Schools (SRS) payments to counties were also extended for two more years. The Secure Rural Schools Act, passed in 2000, provides funding to rural counties and schools located near national forests. Prior to SRS, rural counties and schools received 25% of revenues generated from timber sales on national forest lands. Unfortunately, SRS payments have not always been consistent due to delays in reauthorization by Congress, forcing small communities to operate on smaller budgets. Extending SRS payments for two more years fixes the immediate problem, but a long-term solution is needed for this program that benefits local communities, forests, wildlife, and recreation.

Additional provisions impacting public lands in the appropriations bill include overriding a Ninth Circuit Court decision that required the Forest Service to re-initiate Endangered Species Act consultation with the Fish and Wildlife Service for land and resource management plans. Also, the bill does not include separate funding for the Legacy Roads and Trails program, which was previously funded at $40 million. The Legacy Roads and Trails program has funded road decommissioning, road maintenance and repairs, and removal of fish passage barriers. LRT has benefited aquatic wildlife throughout our national forests, and we are concerned that this program will not be utilized to its full potential without a budget separate from other Forest Service road programs.

Appropriations and other must-pass legislation can become a battleground for public lands, and we will continue to oppose under-the-radar attacks on our bedrock environmental and public participation laws. For further information about the appropriations bill and related public lands issues visit the links below.

• 2018 Appropriations Bill: “Is This Any Way To Drive An Omnibus? 10 Questions About What Just Happened” –NPR

• Wildfire Funding Fix and new Categorical Exclusion: “The Energy 202: Congress finally found a new way to fund wildfire suppression” – The Washington Post

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_gallery interval=”0″ images=”161″ img_size=”full” onclick=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_separator type=”normal” color=”#444444″ thickness=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1465592094531{background-color: #96d1ae !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”125px”][latest_post_two number_of_columns=”3″ order_by=”date” order=”ASC” display_featured_images=”yes” number_of_posts=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Forest Collaborative Groups

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_column_text]In forest collaborative groups, diverse stakeholders including environmental organizations, timber companies, recreational organzations, and other interested members of the community come together to discuss timber sales and other proposed projects with Forest Service staff. Cascade Forest Conservancy is a founding member of, and active participant in, both forest collaboratives in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. The Pinchot Partners, formed in 2003, focuses on projects in the Cowlitz Valley Ranger District, and the South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative, formed in 2011, focuses on projects in the Mt. Adams Ranger District. Through collaborative participation, our goal is to influence GPNF projects to be sustainable for wildlife, fish, water quality, and local communities.

During the warmer months our meetings involve field trips where we can see proposed sale units or projects after they are completed. Seeing how projects look on the ground inspires robust conversations about topics such as riparian habitat, harvest practices, and roads. Last year, the SGPC went on a trip to a temporary road that had been used in a timber sale and obliterated. Seeing this former temporary road led to a discussion about the impacts of temporary roads that is ongoing. The Pinchot Partners visited units for the Iron Crystal timber sale and areas that would be part of huckleberry monitoring efforts. During the huckleberry trip, Pinchot Partners members were able to learn about our huckleberry monitoring process from CFC staff.

During the warmer months our meetings involve field trips where we can see proposed sale units or projects after they are completed. Seeing how projects look on the ground inspires robust conversations about topics such as riparian habitat, harvest practices, and roads. Last year, the SGPC went on a trip to a temporary road that had been used in a timber sale and obliterated. Seeing this former temporary road led to a discussion about the impacts of temporary roads that is ongoing. The Pinchot Partners visited units for the Iron Crystal timber sale and areas that would be part of huckleberry monitoring efforts. During the huckleberry trip, Pinchot Partners members were able to learn about our huckleberry monitoring process from CFC staff.

Another important role of the collaborative groups is to vote on retained receipts funding. This is money generated from selected timber sales that is used to fund restoration activities. Both collaboratives get to vote on our priorities for restoration activities and how much funding should be allocated to these projects. The collaborative groups have chosen to fund high school field work crews, aquatic restoration projects, riparian planting, invasive weed treatments, and many other projects through retained receipts.

Over the last year in the South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative we have worked on the Upper White Salmon timber sale, formed subcommittees to focus on important topics, and began discussing the Middle Wind timber sale. The Upper White Salmon project was located in drier forest near Mt. Adams. A focus of the collaborative discussion in this project was the harvest prescription for mature forest units with large trees. After several meetings we were able to reach a compromise that considered wildlife habitat, the role of fire on the landscape, and the future climate change impacts. The Middle Wind project is located in a part of the GPNF that has many riparian areas and listed fish habitat. We would like to see this project implemented in a way that improves aquatic habitat and reduces road mileage in the watershed. We have also participated in subcommittee meetings to develop a Zones of Agreement document for the group focused on plantations. The intent of that document is to streamline discussion for topics we agree on, and to educate others about the SGPC.

Over the last year in the South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative we have worked on the Upper White Salmon timber sale, formed subcommittees to focus on important topics, and began discussing the Middle Wind timber sale. The Upper White Salmon project was located in drier forest near Mt. Adams. A focus of the collaborative discussion in this project was the harvest prescription for mature forest units with large trees. After several meetings we were able to reach a compromise that considered wildlife habitat, the role of fire on the landscape, and the future climate change impacts. The Middle Wind project is located in a part of the GPNF that has many riparian areas and listed fish habitat. We would like to see this project implemented in a way that improves aquatic habitat and reduces road mileage in the watershed. We have also participated in subcommittee meetings to develop a Zones of Agreement document for the group focused on plantations. The intent of that document is to streamline discussion for topics we agree on, and to educate others about the SGPC.

This year the Pinchot Partners drafted a response to the Iron Crystal Environmental Analysis and developed a huckleberry restoration strategy in partnership with the Forest Service, CFC, and the Cowlitz Indian Tribe. The Iron Crystal response required several long phone calls and in-person meetings to work through the range of values at play in this project. Many of us shared concerns with the analysis prepared by the Forest Service and met with local Forest Service staff to discuss these issues. We were successfully able to submit a letter before the comment period deadline. In addition to our role as a board member of the Pinchot Partners, CFC also began a new partnership with the collaborative through our huckleberry monitoring. Huckleberry is an important plant to the region culturally, recreationally, and economically, and the Pinchot Partners decide huckleberry restoration should be a priority concern for the organization in the coming years. On February 27-28 the Pinchot Partners held their annual meeting in Packwood, WA. The day and a half meeting is full of great discussions and presentations with Forest Service staff, and this year we visited the White Pass Country Museum and learned about the history of the local communities. Last year, the Pinchot Partners celebrated their 15th anniversary. Over the last fifteen years, our dedication to working together on forest projects has made the partners an example for other collaborative groups throughout the region.

Finding common ground can sometimes be slow, challenging work. It often requires balancing environmental, economic, cultural, and recreational concerns and reconsidering what success means for each of us. Successful collaboration relies on a diverse group of stakeholders, representing a full spectrum of user groups, and bedrock environmental laws. Attempts to weaken environmental laws by Congress present a direct threat to the progress collaboratives have made toward rebuilding trust and developing projects that benefit forests and communities. We are encouraged by the progress these organizations have made since their formation, and we look forward to working on future projects together.

Finding common ground can sometimes be slow, challenging work. It often requires balancing environmental, economic, cultural, and recreational concerns and reconsidering what success means for each of us. Successful collaboration relies on a diverse group of stakeholders, representing a full spectrum of user groups, and bedrock environmental laws. Attempts to weaken environmental laws by Congress present a direct threat to the progress collaboratives have made toward rebuilding trust and developing projects that benefit forests and communities. We are encouraged by the progress these organizations have made since their formation, and we look forward to working on future projects together.

Both collaborative groups meet monthly, and the meetings are open to the public.

To learn more visit:

South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative: http://www.southgpc.org

Pinchot Partners: https://pinchotpartners.org/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

With the New Year, Comes a New Project for CFC!

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_column_text]Beavers have a bit of a reputation as being nuisances for landowners. But to us, they are self-adapting ecosystem engineers! For that reason, we are beginning a project with Cowlitz Indian Tribe to reintroduce more beavers into the aquatic ecosystems of Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Beavers are able to build resilience to climate impacts, create wetland and side-channel habitat, and improve water quality for downstream communities. In the face of climate change, events like increased winter streamflow and low summer flows and drought, these furry engineers can help mitigate the impacts of fluctuating streamflows. A newly constructed dam will increase channel complexity and forge new routes of flow. This process also helps keep water in the system for longer periods of time and transfers water to wetland areas that could otherwise become dry. Dams can create more deep pools, which is important for many threatened and at-risk fish species that reside in GPNF. All in all, the reintroduction of beavers a unique and self-adapting way to improve aquatic health and enhance resilience to climate impacts we expect to see in the future.

Our goal with the beaver project is to release 18 – 25 beavers over two years into strategic locations in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. To date, we have carried out site visits with Forest Service biologists and Cowlitz Indian Tribe, begun a spatial analysis to identify optimal release sites, worked with specialists concerning pre-release habitat modifications, planted willows for future beaver forage, and set up plans with local hatcheries to serve as holding facilities for the beavers. Beaver speed dating, anyone? In October, our Young Friends of the Forest participants got the opportunity to visit the forest and gather field data to help assess potential beaver relocation sites. As the year progresses, we will continue to assess more potential beaver relocation sites, and once those sites are chosen, the acquisition of beavers from landowners will begin. From there, beavers will be housed for brief periods of time at local hatcheries, set up with a mate (the beavers will have a higher rate of success in a pair), and then released! Keep an eye on our social media for updates throughout the year. A huge thanks to the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation for helping to fund this project, as well as our many project partners – especially Cowlitz Indian Tribe and U.S. Forest Service.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Protecting Key Habitat Areas of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_column_text]From old-growth forests to snow-covered alpine areas, Washington’s South Cascades are home to a variety of habitat types that support a wide array of plant and animal populations. Connectivity throughout the landscape allows wildlife to move between habitat areas, enabling populations to be more resilient to a changing climate. Cascade Forest Conservancy has identified some of the key areas in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest that, with increased protections, would improve and sustain the ability of wildlife populations to move between patches of habitat and be more resilient to climate change impacts. Increased protections for these areas could range from administrative action, which protects a few select ecosystem values, to designation under the Wilderness Act.

Although there are a variety of approaches for mitigating the impacts of climate change, there is one theme that runs throughout: protect land rapidly to buffer biodiversity against climate change. Climate change is already causing a shift in different forest types, and these impacts are likely to continue in future generations. For current habitat to persist as functional habitat in a changing landscape, reserves and protected areas should be expanded.

Protected areas provide a way to improve connectivity across the landscape by reducing road densities, eliminating some harmful human activities, and otherwise making key habitat areas and corridors available for wildlife. Climate change is impacting habitat by causing a shift in forest types and a decoupling of species relationships. Warmer, drier years are beginning to move forest types north and to higher elevations, and these impacts may be long-lasting on the landscape. Some wildlife populations will need to migrate to adapt to these changes. If there is not suitable habitat nearby, or it is not connected by a corridor of dispersal habitat, events such as a wildfire or drought could wipe out populations. By protecting key habitat areas in the forest through laws, regulations, and other designations, we can help ensure that they remain intact to benefit wildlife populations.

Key areas identified for increased protection in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

To identify priority areas for increased protection in this region, we first located roadless areas to determine where connectivity would be improved by maintaining large roadless areas and smaller connected ones. We also focused roadless areas because Inventoried Roadless Areas already receive some protections under the 2001 Roadless Rule and are good candidates for additional protection. Locating roadless areas on a map also helped to determine where remnant road segments could be removed to benefit connectivity across the landscape. Inventoried Roadless Areas (IRAs) are roadless areas greater than 5,000 acres that have been inventoried by the Forest Service during the Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE) and other assessments. IRAs meet the minimum criteria for designation under the Wilderness Act and are managed in accordance with the 2001 Roadless Rule.

We also located uninventoried roadless areas, which are areas that are predominately roadless, but were not formally inventoried by the Forest Service. Remnant roads, or roads that are closed but still on the Forest Service road system, remain in some uninventoried roadless areas. These remnant roads and roads that lie between two potentially conjoining roadless areas are top priorities for road reduction. To understand where roadless areas exist in relation to habitat core areas and connectivity corridors, we overlaid maps of connectivity corridors on roadless maps. This helps us determine where to focus our climate adaptation efforts to strengthen roadless values and decrease fragmentation.

Based on these maps, and the need for reserves of different habitat types, we identified the following areas as key places for increased protections in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Some of these areas are suitable for designation under the Wilderness Act, but others may be more suited to being protected administratively such as through special area designation or forest plan amendments.

(1) Trapper Creek Wilderness Addition

The “Bourbon Creek” addition to the north side of the Trapper Creek Wilderness contains healthy stands of old-growth forest, and it is currently part of an Inventoried Roadless Area. This Wilderness expansion would provide an important enlargement of contiguous habitat in the southern Gifford Pinchot National Forest and an additional buffer to the surrounding mix of forest lands subject to timber harvest, encroaching forest edges, and roads. Also, there is a lack of Wilderness areas in the GPNF that are easily accessible from population centers. The Trapper Creek Wilderness is a popular location for day-use backcountry recreation, and expansion will enhance those opportunities while also making more habitat available for wildlife. Wildlife camera surveys have shown this area to be well-used by a diverse set of animals and considering the nearby pressures of urban expansion, logging, and habitat shifts, there is good reason to formally establish protection for this area.

(2) Siouxon Creek

The Siouxon Creek area is home beautiful waterfalls and patches of old-growth forest closely intermingled with post-fire habitat created by the many great fires that swept through this area in the early 1900s. These unique features make this area important habitat for many different wildlife populations. Siouxon Creek is also a popular recreation area, and recreation in this area is likely to increase as the nearby population centers in Southwest Washington continue to grow. This important connectivity corridor and popular recreation area would benefit from formal administrative or legislative designation to protect habitat values.

(3) Dark Divide

This iconic roadless area is drenched with more lore and wonder than any other part of the Cascades. This area is thought to be home to Bigfoot, and it was once considered to be the likely landing site of D.B. Cooper, who parachuted from a plane in 1971 with bags of stolen money. Not only is the Dark Divide a landscape of legends, it is also highly important as a habitat reserve for its contiguous old-growth forest stands. Unfortunately, the Dark Divide has been filled with the loud and damaging footprint of off-road vehicles (ORVs). Due to the noise and large ruts created by ORVs, terrestrial and aquatic habitat quality has decreased along with the opportunity for backcountry hiking and camping. The Dark Divide has yet to gain a level of increased protection despite its high value as a large reserve of roadless old growth habitat.

These three areas are a subset of the key areas we have identified for increased protection in the GPNF. A large network of protected areas in Washington’s South Cascades is a long-term goal that will involve partnerships, citizen involvement, and various conservation approaches. Designation of these areas requires working on several levels to increase our understanding of needs and optimal routes for building climate resilience in these forest ecosystems. Many of our on-the-ground efforts will be carried out at the local, ranger district, and regional levels. However, it is also important to continue to advocate for strong national policies as many GPNF projects will be implemented based on national policy. Public involvement in these efforts will be critical. We encourage citizens to write, call, or meet with their congressional representatives and Forest Service officials to advocate for the protection of key natural areas. To learn more about these efforts and CFC’s other strategies to promote climate resiliency in the GPNF, check out our Wildlife and Climate Resilience Guidebook, which can be found by clicking [here][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Press Release: Mining Exploration Approved Near Mount St. Helens

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_separator type=”normal” color=”#444444″ thickness=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][vc_column_text]FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 23, 2017

CONTACTS:

Nicole Budine, Policy and Campaign Manager, Cascade Forest Conservancy, 607-735-3753

Matt Little, Executive Director, Cascade Forest Conservancy, 541-678-2322

Tom Buchele, Managing Attorney, Earthrise Law Center, 503-768-6736

Steve Jones, Board Member, Clark-Skamania Flyfishers, 360-834-1265

Kitty Craig, Washington State Deputy Director, The Wilderness Society, 206-473-2523

Mining Exploration Approved Near Mount St. Helens

Conservation and Recreation Groups Oppose Due to Impacts on Fish, Water Quality and Recreation.

Portland, OR – On August 22, 2017, the Forest Service issued a draft decision consenting to exploratory drilling in the Green River valley, just outside the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument. A coalition of over 20 conservation and recreation groups opposes the project, claiming mining exploration and development will significantly harm wild steelhead populations in the Green River, destroy recreational opportunities in the area, and pollute the water supply of downstream communities. The draft decision begins a 45-day objection period.

“Tens of thousands of people have expressed opposition to this proposal due to its impacts on clean water, native fish, and recreation in and around our most treasured National Monument. Yet the agencies continue to advance this dangerous proposal,” said Matt Little, Executive Director of the Cascade Forest Conservancy. “Allowing mining activities in a pristine river valley alongside an active volcano is simply ludicrous. We will do all we can to stop it.”

Drilling permits would allow a Canadian mining company, Ascot Resources Ltd., to drill 63 drill holes from 23 drill pads to locate deposits of copper, gold, and molybdenum. The project would include extensive industrial mining operations 24/7 throughout the summer months on roughly 900 acres of public lands in the Green River valley, just outside the northeast border of the Monument. The prospecting permits allow for constant drilling operations, the installation of drilling-related structures and facilities, the reconstruction of 1.69 miles of decommissioned roads, and pumping up to 5,000 gallons of groundwater per day.

Some parcels of land in question were acquired to promote recreation and conservation under the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act (LWCFA). In a previous lawsuit filed by the Cascade Forest Conservancy (then the Gifford Pinchot Task Force), a federal judge invalidated Ascot’s drilling permits and held that the agencies violated the LWCFA by failing to recognize that mining development cannot interfere with the outdoor recreational purposes for which the land was acquired. The decision by the BLM and Forest Service to once again issue Ascot drilling permits follows the release of a modified EA earlier this year, prepared in response to this prior court decision.

“This project would severely impact recreation opportunities due to noise, dust, exhaust fumes, lights, vehicle traffic, the presence of drill equipment, and project area closures,” said Tom Buchele, Managing Attorney of the Earthrise Law Center. “I cannot fathom how the Forest Service could legally conclude that drilling would not interfere with recreation without violating the LWFCA.”

The pristine Green River flows through the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, passing through old growth as well as a unique post-eruption environment that provides habitat for a variety of native fish and wildlife. The Green River flows into the North Fork Toutle River and Cowlitz River, which provides drinking water to thousands of people in downstream communities. The city of Kelso recently passed a resolution against the mine because of impacts from leaking mine effluent and failed toxic tailings ponds that would result from locating a mine in an active volcanic zone.

“This prospecting is a threat to wild steelhead in the Green River and the rest of the Toutle and Cowlitz River system,” said Steve Jones, Director, Clark-Skamania Flyfishers. “Washington fisheries managers made the upper Green River a Wild Steelhead Gene Bank in 2014 because this habitat offered the best hope for sustaining wild fish in that system. This river drainage needs to be conserved, not exploited.”

“Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument is a national treasure that offers a unique recreational and educational experience for visitors in the Pacific Northwest,” said Kitty Craig, Washington State Deputy Director of the Wilderness Society. “Its borders are no place for an industrial mine that will jeopardize the free-flowing Green River, the drinking water of downstream communities, and the wide range of recreational opportunities these lands and waters provide.”

###

PROPOSAL DOCUMENTS:

Modified EA: https://eplanning.blm.gov/epl-front-office/projects/nepa/52147/66795/72638/Goat_Mountain_MEA_20151217_FINAL.pdf

Cascade Forest Conservancy (GPTF) et al modified EA comments: https://cascadeforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/FINAL-Goat-Mountain-MEA-Comments_2-4-16.pdf

Forest Service FONSI/Draft DN: http://a123.g.akamai.net/7/123/11558/abc123/forestservic.download.akamai.com/11558/www/nepa/101692_FSPLT3_4050107.pdf

Senator Cantwell Letter to the Forest Service: https://cascadeforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Cantwell-letter-to-Forest-Service-Goat-Mountain-Project_3-18-16.pdf

LEGAL DOCUMENTS:

Judge Hernandez’s Opinion: https://law.lclark.edu/live/files/17566-gifford-pinchot-mining-decisionpdf.

MAPS/PHOTOS:

Map of the Project Area: https://cascadeforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Map-of-Mt-St-Helens-mine-area-zoomed-in.jpg

VIDEO:

Cascade Forest Conservancy “Mount St. Helens: No Place for a Mine” : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JjVk78cVNCk

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_gallery interval=”0″ images=”164,161,145″ img_size=”full” onclick=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1465592094531{background-color: #96d1ae !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”125px”][latest_post_two number_of_columns=”3″ order_by=”date” order=”ASC” display_featured_images=”yes” number_of_posts=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Northwest Old-Growth Forests: Carbon Storage Stars

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_column_text]

By Nicole Budine

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_column_text]Lush, old-growth, conifer forests are an iconic feature of the Pacific Northwest. Large, magnificent trees and brilliant shades of green bring people from near and far to these forests to recreate. Pacific Northwest old-growth forests are beautiful backdrops for recreation, but they also have an important role in mitigating climate change impacts. The Gifford Pinchot National Forest, which has several areas of low elevation mature and old growth forests, is ranked fourth in the nation for carbon storage. Old forests absorb more carbon than young forests because there is a complex ecosystem, with each plant, animal, and fungi playing a role in carbon storage. As part of our climate resilience blog series, this article highlights information on old-growth forests and carbon storage presented in our Wildlife and Climate and Resilience Guidebook.

Northwest Forest Plan

Northwest Forest Plan

Decades of clearcutting left a legacy of young plantations and fragmented old forests. Logging old-growth forests releases a lot of carbon by cutting old trees and disrupting the diverse ecosystem working to store carbon. Thankfully, old-growth logging on our federal public lands in the northwest was mostly halted by the Northwest Forest Plan, created in 1994 in response to the impact of large-scale clearcutting on the federally-protected northern spotted owl. One way the Northwest Forest Plan changed logging on federal lands was by allocating land for the future development of old-growth characteristics, called Late Successional Reserves, or “LSRs.” Management of LSR forests should encourage the future development of old-growth characteristics including downed logs, standing dead trees called “snags,” and diverse understory plants. By encouraging the development of old-growth characteristics in reserves throughout the region, the Northwest Forest Plan protected entire old-growth ecosystems, not just individual trees.

Recovering the Landscape

Although many old-growth forests are safe from clearcutting today, we still have a long way to go to recover from the mistakes of the past. Connectivity between large, biodiverse areas is important to support long-term ecosystem stability in the face of a changing climate, but decades of clearcutting fragmented mature and old-growth forests. By protecting roadless areas and expanding wilderness areas, we can preserve the high carbon storage potential of remaining old-growth forests and improve connectivity across the landscape. The Northwest Forest Plan provides a framework for encouraging the development of future old-growth forests, but it only applies to federally-owned lands. Various landowners working in partnership to promote the development of mature forests will increase carbon storage potential throughout the region.

Mature forests, well on their way to developing old-growth characteristics, are at-risk in controversial clearcutting projects. Forests that are 80 years or older are often already developing the diversity needed to be valuable habitat and climate refugia. Logging these areas, if done at all, should focus on the development of old-growth characteristics. Commercial logging should focus on thinning plantations to improve diversity, as plantations offer little value for either habitat or carbon storage. Management of forests should look beyond their financial value for timber production and also consider their immense value in mitigating the costly impacts of climate change.

Mature forests, well on their way to developing old-growth characteristics, are at-risk in controversial clearcutting projects. Forests that are 80 years or older are often already developing the diversity needed to be valuable habitat and climate refugia. Logging these areas, if done at all, should focus on the development of old-growth characteristics. Commercial logging should focus on thinning plantations to improve diversity, as plantations offer little value for either habitat or carbon storage. Management of forests should look beyond their financial value for timber production and also consider their immense value in mitigating the costly impacts of climate change.

To learn more about the Northwest Forest Plan and forest management in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, visit: https://cascadeforest.org/our-work/forest-management/[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1465592094531{background-color: #96d1ae !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”125px”][latest_post_two number_of_columns=”3″ order_by=”date” order=”ASC” display_featured_images=”yes” number_of_posts=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Big Tree Hunting in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_column_text]

By Darvel and Darryl Lloyd

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_separator type=”normal” color=”#444444″ thickness=”3″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_column_text]My twin brother, Darryl, and I have always loved big trees and old forests. We grew up at our family’s Flying L Ranch near Glenwood, Washington, where we hung out at the ranch’s only old-growth ponderosa pine that we named “The Council Tree.” We always loved to explore the lovely old-growth ponderosa pine stands above the Glenwood Valley and fish in the creeks shaded by big cottonwoods, cedars and firs.

So after we sold the ranch in 1997 and settled down a bit in this new millennium, we began taking trips together throughout the west, always seeking out big trees wherever possible. We especially love the remaining old-growth stands in Gifford Pinchot National Forest, getting to know the area quite well after so many years climbing its peaks and driving its back-roads. Throughout our lives we were always awed by the “Trout Lake Big Tree,” just inside the GPNF and one of the state’s largest ponderosa pines until it died last year).

Our passion for hunting giant trees in the GPNF has increased, especially over six years when we’ve made some significant “discoveries” and brought along a steel measuring tape to measure diameters at average breast height (dbh). We’ve held off purchasing an accurate laser height-measuring instrument because of the cost. In some cases, it has taken Internet sleuthing and difficult bushwhacking with map and compass to find some of the giants. Darryl finally bought a GPS device—hooray!

Here are what we believe to be the GPNF’s largest known western redcedar, two Douglas firs, and noble fir by girth and volume, with a caveat: only a tree climber and/or a forest expert (with an accurate height measuring device) would be able to determine these trees’ exact heights and volumes. Of course, there may be larger trees out there, but someone has to find them.[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_single_image image=”3092″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”right” qode_css_animation=””][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_column_text]1. A giant western redcedar (Thuja plicata) 14’ 3” in diameter at breast height (dbh) and maybe 150 feet tall. We dubbed it “Trinie’s Cedar,” after a young lady who helped us discover and measure the brush-surrounded tree. The huge tree is located off FR 25 in the Cedar Flats Research Natural Area in GPNF, on a terrace of the Muddy River. We challenge anyone to find a larger “cedar” in the GPNF![/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_single_image image=”3095″ img_size=”medium” add_caption=”yes” qode_css_animation=””][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_column_text]2. An equally-giant Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) 11 ft.,10” dbh and about 160’ tall to the shattered top, only around 5 miles from of Randle in an unlogged area of the Cowlitz Valley Ranger District. We called it the “Bob Pearson Fir,” a spotted owl expert who discovered the tree and showed it to us. It’s certainly must be one of the largest-diameter Douglas firs still alive in the Cascade Range.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_single_image image=”3097″ img_size=”medium” add_caption=”yes” qode_css_animation=””][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_column_text]3. An immense “stove pipe” of a Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), 10’ 3” dbh, maybe 250-275 tall. Its the largest tree in the Quartz Creek Big Trees Preserve and probably the GPNF’s largest tree in volume, located not far off FR 26, just outside of the Mt. St. Helens blast zone and inside Lewis County. Unfortunately, the Forest Service is no longer maintaining the loop trail through this very impressive grove, and FR 26 is vulnerable to washouts from strong winter storms.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_single_image image=”3098″ img_size=”medium” add_caption=”yes” qode_css_animation=””][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_column_text]4. The world’s largest known Noble fir (Abies procera) is located in the Goat Marsh Research Natural Area of the Mount St. Helens NVM, in a magnificent 70-acre stand of very large noble firs and Douglas firs (said to contain the highest wood volume per acre of any research plot in the world outside the California coast redwoods). Discovered by Robert Van Pelt in 2001 and named “The Goat Marsh Giant”, the tree measures 8’3” dbh and approximately 265 ft. tall, with a dead top reducing the height since Van Pelt measured it. It has almost reached the end of its life (age around 300-350 years).[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_single_image image=”3099″ img_size=”medium” add_caption=”yes” qode_css_animation=””][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1465592094531{background-color: #96d1ae !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”125px”][latest_post_two number_of_columns=”3″ order_by=”date” order=”ASC” display_featured_images=”yes” number_of_posts=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Defend Public Lands from Lawless Logging

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”1250″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” qode_css_animation=””][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][vc_column_text]

TAKE ACTION to stop a dangerous forest bill!

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator type=”normal” color=”#444444″ thickness=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”15px”][vc_column_text]You can help protect our national forests by speaking out against the so-called “Resilient Federal Forests Act of 2017” (HR 2936). Unfortunately, this bill recently passed the House Natural Resources Committee, and will soon come up for a vote before the House. Now is the time to make public opposition to this bill known, please contact your representative and urge them to vote NO on HR 2936!

Representatives to contact:

–Jaime Herrera-Beutler (WA-3rd District)

–Kurt Schrader (OR-5th District)

–Greg Walden (OR-2nd District)

–Find your representative

This is one of the worst pieces of federal forest legislation in recent history, and favors logging at the expense of other public land values such as recreation, fish and wildlife habitat, and drinking water for local communities. Here are three ways this bill would harm public lands.

(1) Allow logging up to 30,000 acres without consideration of environmental impacts

If this bill passes, it will exempt many logging projects up to 10,000 acres from complying with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and up to 30,000 acres if the projects were developed in a “collaborative process.” By exempting these projects from NEPA, large areas of the forest could be cut without in-depth consideration of the environmental impacts. This would undermine decades of work to ensure diverse public land values are considered and protected on federal forests.

(2) Weaken Endangered Species Act protections

The Endangered Species Act requires the Forest Service to consult with the National Marine Fisheries Service and/or the Fish and Wildlife Service whenever they propose a project that could harm a listed species. These agencies are the federal experts on the Endangered Species Act, and the consultation requirement helps the Forest Service consider potential impacts to listed species. This bill would eliminate the consultation requirement, allowing the Forest Service to decide whether or not to consult or not on a project, and completely exempt other forest management projects from the Endangered Species Act.

(3) Limit public input and judicial review of agency decisions.

Public input is essential to creating projects that balance diverse values on federal forest lands. HR 2936 would disrupt this balance by restricting the ability of citizens to comment on projects and the ability to challenge agency decisions in court. The bill would limit public comment periods to only 30 days and allow the Forest Service consider only two alternatives – no action or intense logging. The bill also forces citizens to challenge decisions through a binding arbitration process, which means that the agency can escape litigation even when they clearly violated the law. It also would prevent courts from temporarily stopping salvage logging projects while deciding a case and prevent plaintiffs from recovering attorney’s fees, even if they are successful in court.

This bill would increase logging without considering environmental concerns, directly threatening public lands and the many values they provide. Please contact your representative and ask them to vote NO on HR 2936.

- Find your representative

- Read the bill

- Learn more about forest management and current timber sales in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_gallery interval=”0″ images=”1308″ img_size=”full” onclick=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_separator type=”normal” color=”#444444″ thickness=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_empty_space height=”150px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1465592094531{background-color: #96d1ae !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”125px”][latest_post_two number_of_columns=”3″ order_by=”date” order=”ASC” display_featured_images=”yes” number_of_posts=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Road Restoration on Forest Lands

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_column_text]

By Shiloh Halsey and Nicole Budine

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_column_text]Road restoration can offer many benefits for wildlife and ecosystems. People also benefit from an improved and simplified national forest road system! Road restoration can include everything from updating and repairing roads to closing or fully decommissioning them.

Presently, there are over 4,000 miles of roads in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, enough to go to Texas and halfway back. Many of these are not used or needed but remain on the system, impacting wildlife in a variety of ways.

The Ecological Effects of Roads

Roads can fragment habitat, increase sediment in streams, block stream connectivity, and increase the spread of invasive plants. Also, when there are too many roads to maintain, they can end up washing out, which can affect fish and wildlife populations, water quality and access to our favorite places in the forest.

Climate change is likely to exacerbate many of the negative impacts from roads, especially by increasing the amount and severity of high streamflow events. We need to work to ensure that our road network is resilient to these projected changes.[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”10px”][vc_column_text]

What we can do to improve Watersheds and Habitats

We are working to update our knowledge about the current status of roads in the Gifford Pinchot by leading road surveys to locate blocked culverts, measure erosion, and help prioritize which roads are optimal candidates for repair or closing.

Blocked culverts negatively impact stream connectivity and fish habitat, and they can cause roads to wash out, which is a substantial expense both financially and ecologically. Areas of erosion, such as when water running along gravel roads and back into streams, brings heavy loads of sediment into waterways, affecting fish and water quality for downstream communities.

We are also working with stakeholder groups and the U.S. Forest Service to incorporate road restoration into forest management projects. Generally, we believe that reducing the amount of road miles should be one of the restoration activities associated with each timber harvest project. This is often cost- and time-effective because the federal review processes for both timber harvest and road projects can be combined into one effort.

Also, since road work would be occurring at the same time as other actions, the impact from active management would be less. Road closures and decommissioning should also be considered for stand-alone projects. CFC is part of a broader network, called The Washington Watershed Restoration Initiative (WWRI), which is aimed at bringing in federal funds for local road restoration projects.

How we are Restoring Habitats

Road decommissioning efforts should be coupled with planting of native species along the former road to speed up regrowth and decrease continued impacts from erosion. This work is sometimes carried out by the Forest Service or local contractors, as it is written in the road improvement plan.

Other times, volunteers can get involved and assist with the planting efforts. Because there is such a great need for road restoration and the work involves heavy machinery and skilled labor, it can be an important economic driver for contractors that specialize in road improvement projects. We feel that road restoration should be prioritized for contractors in local communities that surround the forest.

Check out our list of stewardship trips at the link below and sign up for a road survey this summer! To support our work, we also encourage you to become a member of the Cascade Forest Conservancy.

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1465592094531{background-color: #96d1ae !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Climate Projections for Washington's South Cascades

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_empty_space height=”50″][vc_column_text]

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”20″][vc_column_text]

As is the case with any modeling process, climate projections can vary. There are, however, many areas of agreement among the various climate models and these projections offer a warning for those of us hoping to protect our natural resources. The projections also highlight opportunities to protect habitat and wildlife. Some aspects of our local ecosystem will likely not fare well under changing conditions, yet others are expected to do fine. For many species and habitat types, there are conservation and restoration steps that we can take to mitigate harm and help them persist.

As is the case with any modeling process, climate projections can vary. There are, however, many areas of agreement among the various climate models and these projections offer a warning for those of us hoping to protect our natural resources. The projections also highlight opportunities to protect habitat and wildlife. Some aspects of our local ecosystem will likely not fare well under changing conditions, yet others are expected to do fine. For many species and habitat types, there are conservation and restoration steps that we can take to mitigate harm and help them persist.

Throughout the pages of our Wildlife and Climate Resilience Guidebook, we highlight opportunities for organizations, managers, and the public to do their part to protect species and their habitats. Our first step in this process, though, was identifying what changes we can expect to see in the southern Washington Cascades. In this article, our second in the climate resilience blog series, we outline these findings.

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”20″][vc_column_text]

Climate Impacts

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”20″][vc_column_text]

Climate projections for the southern Washington Cascades indicate that average temperatures will rise, summer water availability will decrease, high streamflow events during winter will increase, and snow cover will decrease. These changes will impact both aquatic and terrestrial environments.

By the later decades of this century, temperatures for the Columbia River basin are expected to rise anywhere from roughly 0.5° to 8°C (1° to 15°F) above 20th century averages. Changes in temperature and weather patterns will cause habitat locations to shift, increase the forest’s susceptibility to insects and wildfire, and impact the life cycles of plants and animals, likely causing some species to die off. During recent decades, there has been an increase in the size and severity of fires and insect outbreaks  throughout the western United States; further increases, up to 2- to 4-fold, are expected in the coming century. Higher temperatures will cause streams to warm and will threaten a variety of aquatic species, especially salmon and bull trout.

throughout the western United States; further increases, up to 2- to 4-fold, are expected in the coming century. Higher temperatures will cause streams to warm and will threaten a variety of aquatic species, especially salmon and bull trout.

Changing seasonal climate patterns will have a significant effect on ecosystems. A decrease in summer streamflow and more rain falling during fall and winter will be a significant factor affecting habitat availability and the volume/flow of streams and rivers. High streamflow events, for instance, can scour streambeds and wash away fish eggs. Dry streambeds in summer can severely affect a wide array of aquatic and riparian species, from amphibians to mammals to amphibians to fish. Extreme droughts and flooding are expected to occur with greater frequency and magnitude in the coming decades. A reduction in snow pack will affect stream temperatures. In addition, peak runoff from snowmelt is expected to occur 3-4 weeks earlier than current averages, thereby disrupting relationships between a species’ life cycle and that of the hydrologic cycle. With more winter precipitation falling as rain instead of snow, terrestrial habitats near tree line will move upward in elevation, if they can. This shift is also expected to result in a longer growing period in higher elevations.

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”20″][vc_column_text]

Resilient Communities

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”20″][vc_column_text]

In addition to the ecological impacts, climate change is expected to negatively affect local communities and infrastructure. Wildfires can reduce air quality or burn structures at the forest-residential interface, loss of snow can impact recreation tourism, drier summers can affect agriculture, warming waters can degrade fishing opportunities, and high flow events can wash out roads, reduce water quality, or flood croplands. There are, however, ways to mitigate and decrease the likelihood of some of these costly events. Many of these are outlined in our Wildlife and Climate Resilience Guidebook. And through these mitigation efforts, there are economic opportunities for local communities in the form of restoration work and other jobs in the forest.

Forest jobs are an integral part of the heritage of many communities that live within and around the forests of the Pacific Northwest. With the potential for significant job creation, resilience-building projects in the southern Washington Cascades should be prioritized for local community members, businesses, and contractors. Potential employment includes stewardship contracting, road maintenance and decommissioning, forest and river restoration, preparation steps for prescribed burning, and planting of diverse tree species in anticipation of climate change.

There is a lot we can do to decrease many of the negative impacts of climate change. Let’s get to work! www.cascadeforest.org/get-involved/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]