Last week, more acreage in Washington burned during a single day than had during the last 12 years combined. Record-breaking fires are burning across the West. Our thoughts are with the thousands of people who have been forced to make the painful decision to flee their homes, not knowing if they will ever see them again. Entire communities have been destroyed, and people have even lost their lives.

You can help people affected by fires by donating to the Red Cross Western Wildfire Relief fund here.

FIRES ARE A NORMAL PART OF FOREST ECOLOGY IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST, BUT THESE FIRES ARE DIFFERENT. WHY ARE THESE FIRES SO DANGEROUS, AND WHAT CAN WE DO ABOUT IT?

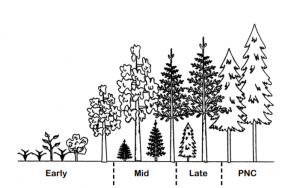

Wildfires shaped the evolution of the plants and animals in our region and remain important to our region. Healthy Pacific Northwest forests are complex patchworks of stands in various stages of growth and regrowth. They are young and old, disturbed, undisturbed, and ever-changing. One reason they look this way is that wildfires do not burn through an area uniformly. Some forest stands in fire-affected areas will ignite while others escape untouched. The resulting mosaic of varied habitats supports diverse communities of plants and animals including some species that thrive in these unique post-fire conditions.

But studies are showing that today’s fires are more intense, and some are burning the same areas in quick succession, compared to historic patterns. These “short-interval”, high-intensity fires are negatively affecting increasingly rare old-growth stands, which are evolved to be resilient to fire, but can still be damaged by high intensity and repeated burns. These fires are also making it harder for affected areas to bounce back by depleting seed banks, and eroding forest soils. CFC staff have seen firsthand what scientists are describing. Some of the post-fire areas we’ve visited that should have been sites of vigorous regrowth were recovering slowly and with low biodiversity compared to what we typically expect to see.

But studies are showing that today’s fires are more intense, and some are burning the same areas in quick succession, compared to historic patterns. These “short-interval”, high-intensity fires are negatively affecting increasingly rare old-growth stands, which are evolved to be resilient to fire, but can still be damaged by high intensity and repeated burns. These fires are also making it harder for affected areas to bounce back by depleting seed banks, and eroding forest soils. CFC staff have seen firsthand what scientists are describing. Some of the post-fire areas we’ve visited that should have been sites of vigorous regrowth were recovering slowly and with low biodiversity compared to what we typically expect to see.

A major contributing factor to the current situation with wildfires is ongoing climate change. Rising temperatures and changing weather patterns have left our forests particularly dry and warm. “Forest fuels” are as dry as they’ve ever been, and are releasing more energy when ignited, meaning fires are hotter, more destructive, and more unpredictable. In Oregon and Washington, big fires usually occur less frequently on the west side of the mountains and more commonly in more arid climates east of the Cascades. This year’s drought conditions have enabled fires to burn in areas close to major population centers west of the Cascades—areas that are too damp to sustain major burns most other years. Although climate change is the primary reason fires in the west are getting worse, it is not the only factor.

Not only are fuels drier and more volatile, they are also more abundant across our forests. For generations, indigenous people used controlled fires to sustainably manage the forests in the Pacific Northwest. But settlers and colonizers dangerously mismanaged the forest to devastating effect. Federal and State government agencies adopted policies of universal fire suppression and other unsustainable forestry practices. Across America, many fire-resilient, biodiverse old-growth forests have been clear-cut and replaced with crowded, overgrown, homogeneous, single-species stands of trees designed to grow fast and be harvested for maximum profits. Over the last hundred years, responsibly managed, dynamic, and healthy forest ecosystems have been systematically replaced by what is essentially a tinderbox.

What can be done to prevent severe fires in the future?

What can be done to prevent severe fires in the future?

One of the most commonly proposed solutions to the problem is thinning. But thinning these forests alone doesn’t help and in many cases, it exacerbates the problem. Thinning that focuses on removing large trees—the most fire-resistant material—will do more harm than good from a fire resilience perspective. Responsible thinning in conjunction with prescribed burns, like the current work happening to protect old-growth ponderosa pine and douglas fir stands south of Mt. Adams, can do a lot to protect mixed conifer forests from wildfire. While these and similar methods can help protect specific stands in certain types of mixed conifer forests, this doesn’t apply universally to all forests in the western US and there is no realistic way to continually protect 350 million acres of overgrown forests from severe fires.

The problem of intensifying wildfires is a complicated one, and no single solution will work in every forest. The effects of climate change will likewise not be the same for every forest, but will continue to cause universally destabilizing effects. Our best chance to prevent the situation from becoming worse is to do all we can now to stop or slow climate change. Fire-proofing homes and properties in forested areas is another important step for reducing the life-changing impacts of these types of fires.

We expect unusually large and severe fires in our region to continue happening, so Cascade Forest Conservancy is working to help make our forest more resilient to fires now to mitigate some of the damage when it does happen. We address the issue using a wide variety of tools, from scrutinizing proposed timber sales to ensure they account for insights from current ecology and climate science, to working on-the-ground to restore habitats to more natural conditions, therefore reducing the risk of catastrophic burns. For example, post-fire seeding can help kickstart regrowth and biodiversity in areas impacted by successive fires, and dams built by beavers we reintroduce help store water higher up in watersheds, which slows some of the drying resulting from climate change and helps create fire breaks.

TAKE ACTION

Do your part to help elect local, state, and federal officials who believe in climate science and will fight to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and conserve our forests.

Take steps to reduce your carbon footprint.

But

But

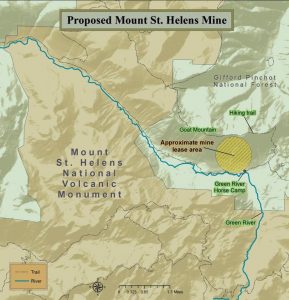

Drilling exploratory boreholes will cause significant negative impacts on the area and the people who enjoy it. The Ascot proposal involves reactivating old roads in pristine forest to transport trucks and heavy equipment to drill sites. Harmful chemicals would be used at the drill sites, some of which are located within 100 feet of waterways, and the constant noise of equipment would disturb wildlife and ruin some of the best fishing, hunting, hiking, horseback riding, and outdoor recreation opportunities in Washington State.

Drilling exploratory boreholes will cause significant negative impacts on the area and the people who enjoy it. The Ascot proposal involves reactivating old roads in pristine forest to transport trucks and heavy equipment to drill sites. Harmful chemicals would be used at the drill sites, some of which are located within 100 feet of waterways, and the constant noise of equipment would disturb wildlife and ruin some of the best fishing, hunting, hiking, horseback riding, and outdoor recreation opportunities in Washington State.

This year, the project will benefit from an additional partnership. Researchers from Washington State University Vancouver are working on a new way to track beavers and understand their impacts, one that uses environmental DNA taken from water samples. The researchers will be working with the beavers who pass through our new facility and tracking them post-release. The new technique they are developing could be key to monitoring wild and reintroduced beaver populations without having to physically track down individual animals.

This year, the project will benefit from an additional partnership. Researchers from Washington State University Vancouver are working on a new way to track beavers and understand their impacts, one that uses environmental DNA taken from water samples. The researchers will be working with the beavers who pass through our new facility and tracking them post-release. The new technique they are developing could be key to monitoring wild and reintroduced beaver populations without having to physically track down individual animals.