By Amanda Keasberry | Science and Stewardship Manager

April 16, 2020

Many of our important stewardship and restoration projects rely on the generosity of volunteer citizen scientists who join us in the forests of Washington’s south Cascades. April is Citizen Science Month, and I recently began to wonder more about the origins of citizen science, and why it’s become so popular today. So here is a quick dive into the fascinating history of citizen science!

“In citizen science, the public participates voluntarily in the scientific process, addressing real-world problems in ways that may include formulating research questions, conducting scientific experiments, collecting and analyzing data, interpreting results, making new discoveries, developing technologies and applications, and solving complex problems” (citizenscience.gov).

The first mention of ‘citizen scientist’ appeared in a 1979 New Scientist article by James Oberg. Oberg wrote about his skepticism that ufology, the study of unidentified flying objects, could be called science and argued that those who studied this “science” were “crackpots and cranks,” whom he later referred to as “citizen scientists.” The first mention of the term was drenched in sarcasm, but nonetheless, those were people of the general public making new discoveries (people just might not agree on what those discoveries actually were…). The term ‘citizen scientist’ was not seen again in writing until 1989 when it was officially used by the Audubon Society to describe a group of 225 volunteers who helped collect rain samples to assist with an acid-rain awareness campaign.

But long before the term ‘citizen science’ was ever used, there were many amateur and non-professional scientists who volunteered their time to further scientific understanding and exploration. Some of these amateurs are now considered some of the most renowned scientists of all time, like René Descartes, Charles Darwin, and Issac Newton. All of them began as independent, amateur scientists who were initially headed down a different career path. But their intrigue for science led them to discoveries of fundamental scientific concepts and theories which continue to shape our understanding of our world to this day. By the 20th century, science was mostly taken over by professional scientists and researchers who obtained funding through universities and governmental agencies. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the bureaucracy of science research was being brought into question, and the revival of the amateur scientist was being advocated for.

By the 1990s, the use of ‘citizen science’ began to take off and there was an increase in the number of citizen projects, the variety of projects, and the size and scope of projects. Volunteers were being used across all fields and disciplines–making important contributions everywhere from astronomy to oceanography and everything in between. Today the number of citizen science participants have grown even more thanks to technological advancements. Advances like the internet and the creation of mobile smartphones have not only made information easier to obtain, but have created new ways for researchers to engage with large groups of people. For scientists who rely on data collected from the field, smartphones and their connectivity to the internet and their internal global positioning systems have greatly increased the ease of collecting data anywhere in the world. Volunteers are making huge contributions to our knowledge, whether gathering data from their own backyards or in the most remote places of the forest.

By the 1990s, the use of ‘citizen science’ began to take off and there was an increase in the number of citizen projects, the variety of projects, and the size and scope of projects. Volunteers were being used across all fields and disciplines–making important contributions everywhere from astronomy to oceanography and everything in between. Today the number of citizen science participants have grown even more thanks to technological advancements. Advances like the internet and the creation of mobile smartphones have not only made information easier to obtain, but have created new ways for researchers to engage with large groups of people. For scientists who rely on data collected from the field, smartphones and their connectivity to the internet and their internal global positioning systems have greatly increased the ease of collecting data anywhere in the world. Volunteers are making huge contributions to our knowledge, whether gathering data from their own backyards or in the most remote places of the forest.

CFC has greatly benefited from being able to use smartphones and tablets when out in the field to collect geospatially-referenced data that we can easily share with our partners and the community. Using smartphones or tablets also allows for a uniform way to collect data. We tend toward simplicity in survey design and clarity in the data collection process to ensure quality and consistent data is collected. The quality of data collected by citizen scientists often raises concern among researchers. Some researchers discredit citizen science work, while others believe volunteers can collect comparable data to that of professional scientists. CFC believes there is a huge benefit to public involvement in science and restoration projects and that, in addition, it helps build support from the community for important restoration and conservation work. Citizen science has been an integral part of many of our projects like huckleberry monitoring, beaver habitat site assessments, and the wildlife camera surveys.

We could not gather as much data without the help of citizen scientists, and I know this is the case for other organizations, agencies, and researchers.

Most citizen science projects, including ours, are put on hold right now. But there are actually plenty of citizen science opportunities that you can participate in from the comfort of your home. I will be posting a tutorial for a fun project related to climate change that you can participate in right in your backyard or neighborhood. By participating in this project, you will provide researchers with a more robust dataset which will help them to answer some of the unknowns about climate change. Stay tuned for the video on Friday!

Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World

Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World

All That the Rain Promises and More…

All That the Rain Promises and More…

Desert Solitare

Desert Solitare The Book of Fire

The Book of Fire Sea and Smoke: Flavors from the Untamed Pacific Northwest

Sea and Smoke: Flavors from the Untamed Pacific Northwest The Man Who Planted Trees

The Man Who Planted Trees

A Walk in the Woods

A Walk in the Woods The Lorax

The Lorax Indians of the Pacific Northwest: From the Coming of the White Man to the Present Day

Indians of the Pacific Northwest: From the Coming of the White Man to the Present Day Gifts of the Crow: How Perception, Emotion, and Thought Allow Smart Birds to Behave like Humans

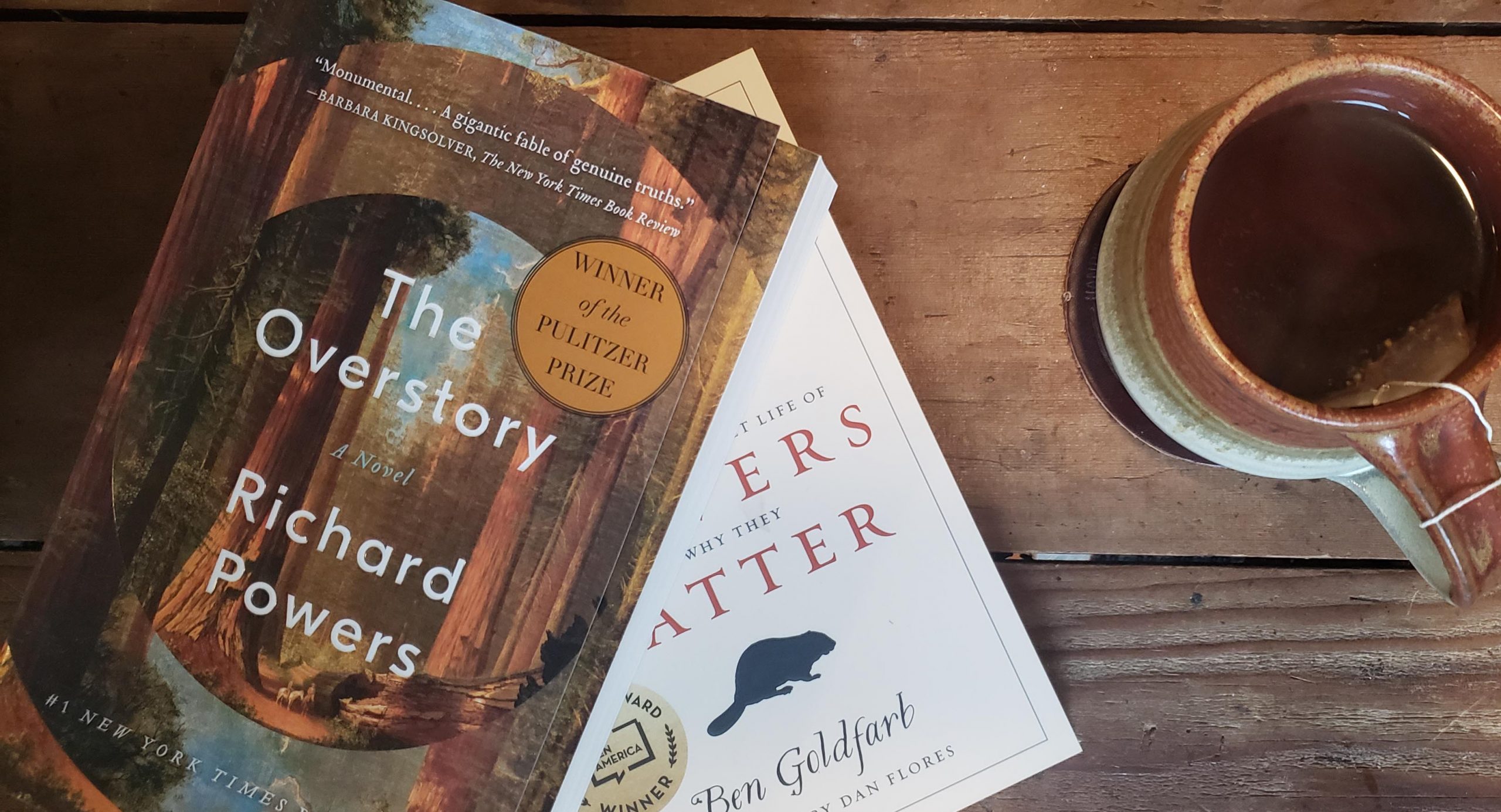

Gifts of the Crow: How Perception, Emotion, and Thought Allow Smart Birds to Behave like Humans The Overstory: A Novel

The Overstory: A Novel Inside Passage: A Journey Beyond Borders

Inside Passage: A Journey Beyond Borders Ever Wild: A Lifetime on Mount Adams

Ever Wild: A Lifetime on Mount Adams Sand County Almanac

Sand County Almanac Where Bigfoot Walks: Crossing the Dark Divide

Where Bigfoot Walks: Crossing the Dark Divide The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America

The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America The Invention of Nature

The Invention of Nature  Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast

Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast The Poetic Inventory of Rocky Mountain National Park

The Poetic Inventory of Rocky Mountain National Park

The US Forest Service has put forward plans to build a road through the heart of this irreplaceable landscape. The proposed road is a threat to the area’s streams, rivers, and lakes. If built, this road will pass over five permanent streams and 10 seasonal streams which together represent five separate watersheds, wholly created after the 1980 eruption. Pristine newborn watersheds like these do not exist anywhere else on earth. The proposed road would lead to soil erosion and deliver harmful sediment into streams and, subsequently, into Spirit Lake. Worse still, each stream-crossing would likely wash out every season, requiring excavation and rebuilding. All this sediment will force aquatic insects and fish to move downstream, negatively impact water quality, and damage stream and lakebed habitats.

The US Forest Service has put forward plans to build a road through the heart of this irreplaceable landscape. The proposed road is a threat to the area’s streams, rivers, and lakes. If built, this road will pass over five permanent streams and 10 seasonal streams which together represent five separate watersheds, wholly created after the 1980 eruption. Pristine newborn watersheds like these do not exist anywhere else on earth. The proposed road would lead to soil erosion and deliver harmful sediment into streams and, subsequently, into Spirit Lake. Worse still, each stream-crossing would likely wash out every season, requiring excavation and rebuilding. All this sediment will force aquatic insects and fish to move downstream, negatively impact water quality, and damage stream and lakebed habitats.