In the Spring of 2023, we shared some exciting news: wolves had finally returned to southwest Washington after a century of absence. The state’s Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) confirmed that a male, WA109M, and an adult female had been seen traveling together in winter (meeting the state’s definition for a pack) in a sparsely populated area along the southeastern border of the Yakama Reservation.

Sadly, the Big Muddy Pack, named for the Big Muddy River, is no more.

Beginning in October 2023, monthly WDFW monitoring reports began to note that agency officials were unable to locate the pack’s female. Months later, the Washington Gray Wolf Conservation and Management 2023 Annual Report, released April 2024, confirmed what some had feared: southwest Washington no longer had a wolf pack. Then this October, WDFW, along with the US Department of Fish and Wildlife confirmed that both members of the pack have been illegally killed and are offering a $10,000 reward for information related to the death of either animal.

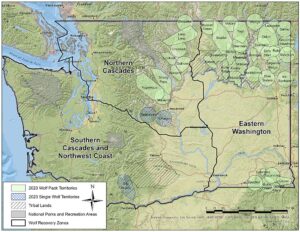

The protected status of gray wolves, both federally and at the state level, is contentious. Here in Washington, a species recovery plan adopted in 2011 divided the state into three regions; Eastern Washington (where the majority of the state’s wolf population reside), Northern Cascades, and Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast. The state’s recovery plan calls for the presence of two breeding packs in each of the three regions for three consecutive years prior to delisting. So far, that condition has not been met. There are currently 33 confirmed packs in the Eastern Washington and Northern Cascades.

Washington’s overall wolf population is on the rise, despite the loss of the Big Muddy Pack and the enduring absence of wolves in the South Cascades and Northwest Coast recovery region. The state’s latest report shows wolf numbers are up 20% since the previous count in 2022, which, this February, led WDFW to formally recommend that the state reclassify wolves from “endangered” to “sensitive.” So far, no changes to wolves’ protected status has been made.

Wolves are a keystone species and their presence can lead to a cascade of positive ecological impacts in the areas they occupy. The loss of the Big Muddy Pack is a setback for the species’ recovery in southwest Washington, but it’s not the end of the story. As the population of wolves in other parts of the state grows (provided adequate protections remain in place) it is all but inevitable that other wolves will travel south and west, seeking territories of their own. The deaths of WA109M and his mate, as well as the ongoing efforts to delist the species, illustrate that the strong feelings people and policymakers have about the presence of wolves will shape their future and that their protected status is far from settled.