A long-absent keystone species has returned to southwest Washington. On April 7th, 2023, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife released a report that confirmed the existence of a new wolf pack in a sparsely populated area on the Yakama Reservation, east of Mt. Adams.

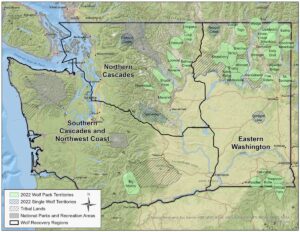

Migrating wolves began returning to Washington in the 2000s from packs in Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Oregon, and British Columbia. Their recovery has been closely monitored ever since. Washington’s Wolf Conservation and Management Plan divides the state into three zones, Eastern Washington (where most of the state’s wolves reside), Northern Cascades, and Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast. The Big Muddy Pack (named by the Yakama Nation for the Big Muddy Creek which flows east from Mt. Adams) is the first pack to establish a territory in the Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast zone.

So far, the Big Muddy Pack consists of only two individuals. One is a young male, WA109M, who set off from his central Washington pack in 2021 and eventually wandered more than 300 miles to Klickitat County. In April 2022, biologists observed WA109M traveling with another wolf who was later confirmed to be female. Two wolves traveling together in winter meet the state’s definition for a pack. The pair have now established a territory and it’s possible they will have pups soon.

As modest as the Big Muddy Pack may be for the moment, the documentation of a new wolf pack in southwest Washington is historic news that many have been waiting a long time for.

Wolves were nearly eradicated across the continental U.S., including within the Pacific Northwest, by the first part of the 20th century. The gray wolf was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act when it was passed in 1973 and listed as endangered by the state of Washington in 1980. The species briefly lost its federally protected status in January 2021, but protections were restored in February 2022.

As the recent back-and-forth protection status changes illustrate, the wolf, perhaps more than any other animal in North America, elicits strong feelings and spurs passionate debates. To some, the federal government’s all-too-successful campaign to exterminate the gray wolf epitomizes the darkest and most ill-informed parts of America’s legacy of colonial expansion and the ecological destruction wrought by people who saw the natural world as something to be claimed and tamed. For them, the return of wolves is a sign that we are moving beyond old ways of thinking and allowing the natural world to heal. For others, wolves represent an unwelcome danger or a threat to rural livestock economies. There are effective co-existence strategies and compensation policies that ranchers and agencies can employ, but fear and distrust often end up taking center stage in some corners.

Wherever they appear (or reappear), the presence of wolves makes an impact, but not just symbolically or politically. Wolves are a keystone species that play a vital role in and bring balance to ecosystems. For example, the now-famous 1995 reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park led to a surprising number of positive impacts for ecosystems in the region. Without their primary predator, elk had overgrazed much of the park. The resulting loss of vegetation negatively impacted populations of mice and rabbits, as well as the animals that prey on them. Songbirds found fewer available nest sites. Even bears were impacted as the elk out-competed them for the berries they relied on. In riparian areas throughout the park, the absence of wolves had even more drastic impacts. Overgrazing in riparian areas led to erosion and stream sedimentation and a reduction of the abundance of beavers, fish, insects, birds, and river otters, compromising the health of entire aquatic systems. With wolves back in the mix, the ecosystem rebounded.

We can see the impacts that a century of elk and deer populations living without their main predator have had on riparian systems here in the southern Washington Cascades as well. It will take more than one pack of wolves to really affect the feeding and movement behaviors of their prey species, but we expect this relationship to be re-established at some point in the future. We look forward to the opportunity to assess how the return of wolves impacts ecosystems here and to better understand the role the species may have to play in supporting climate change resilience in our region.