Mining reform is currently a hot topic, particularly in Washington D.C. There is a growing national conversation about how best to obtain critical minerals needed to fuel the green energy transition while protecting the environment and communities. There are major challenges that we must address to do so. The laws currently governing mining on federal public lands are a patchwork of requirements that make it extremely difficult to ensure hardrock minerals are mined responsibly on those lands.

Policymakers are grappling with what to do about these badly outdated laws, many of which are rooted in a historical legacy of colonial racism and antagonism against the natural world. We know better alternatives to those laws are possible. Change is on the horizon, which means this is the time for the public to get informed and get involved.

HISTORY OF HARDROCK MINING LAWS IN THE U.S.

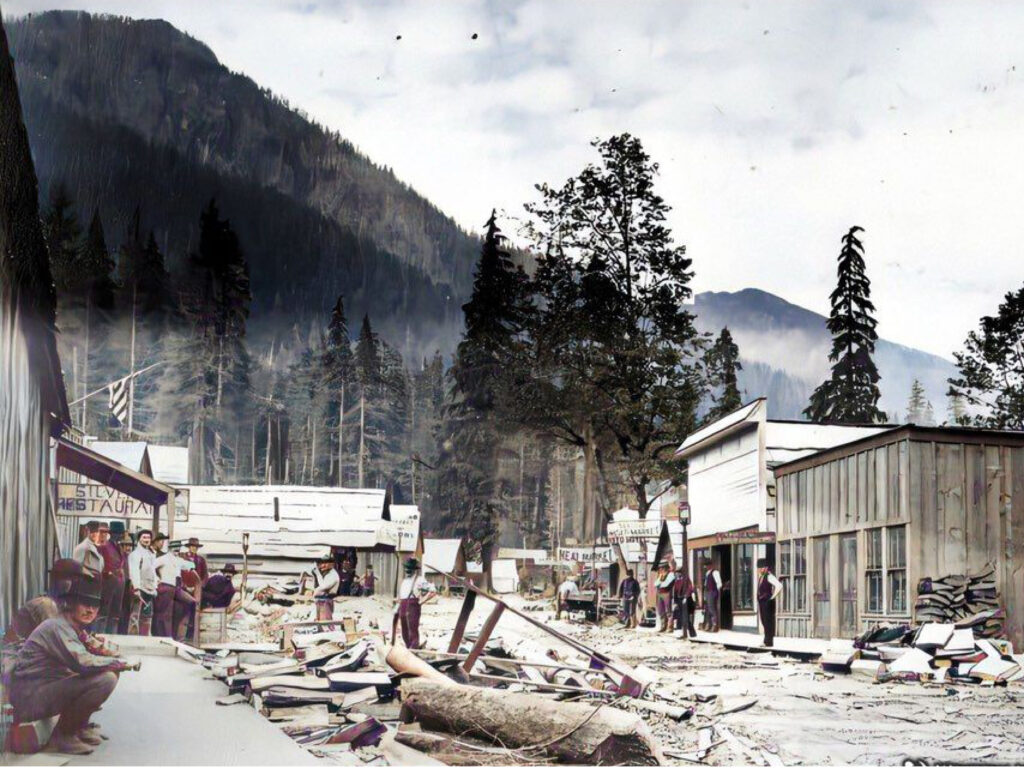

In the 1800s, the United States enacted policies to encourage people to “develop” and colonize the West, including the General Mining Law of 1872. This statute was grounded in manifest destiny and other beliefs we recognize as racist, harmful, and wrong. The 1872 law gave lands to mining developers (at very little cost) that had been taken from Indigenous communities.

Once a claim was patented, the government would recognize a miner’s right to extract minerals –regardless of any other considerations. When the law was passed, the value of the nation’s currency was tied to physical gold (and would remain so until 1971). It’s not surprising then that in addition to giving away land, this statute gave preferential treatment to mining over other land uses.

Over time, small changes were added to the mining regulatory structure. The government created a different structure for regulating mining on federal lands acquired after the act was passed. Mineral rights in these areas can be leased rather than claimed–which gives land managers limited discretion over mining activities compared to claims on lands regulated by the original 1872 General Mining Law.

The last significant update to the system of regulations governing hardrock mining activities was the Mining and Mineral Policy Act of 1970. 1970 was also the year of the first Earth Day. The conservation movement was gaining momentum and there was broad bipartisan support for laws protecting the environment–but the gold standard had not yet been repealed and the government continued to place a high priority on extracting hardrock minerals.

The 1970 policy made it clear how important extracting hardrock minerals remained to the US government. It stated “that it is the continuing policy of the Federal Government, in the national interest, to foster and encourage private enterprise in (among other goals) the development of domestic mineral resources and the reclamation of mined land. This Federal policy obviously applies to National Forest System lands.”¹

Centuries of bad laws regulating mining caused a massive amount of legacy pollution that is still around today. Abandoned hardrock mines have been a known problem for years and a strain on taxpayers due largely to the fact that the General Mining Law of 1872 did not include any environmental protections or cleanup requirements. And unlike regulations governing other extractive industries like oil and gas, the law does not require royalty payments to the government, which could have helped offset the costs of pollution and cleanup taxpayers incur.

Unsurprisingly, the West is littered with abandoned mines. According to the Environmental Protection Agency “[m]ining in the western United States has contaminated stream reaches in the headwaters of more than 40 percent of watersheds in the West.” Sadly, it is often the wildlife and communities living nearby who suffer the environmental and health consequences.

HARDROCK MINING ON FEDERAL LANDS TODAY

Today, hardrock mining is still primarily regulated by the 150 year-old General Mining Law and the 1970 policy. In other words, mining continues to get preferential treatment over other land uses and mining companies continue unnecessarily harming environments and communities while facing little or no accountability. This has been true even in many cases when the decision-making agencies have some discretion.

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Forest Service (USFS) have the discretion to deny mining operation permits in mineral leasing applications. A long and contentious decision making process about mineral leases near the Boundary Waters may become a sign that positive change is starting, but the use of discretion has not been the norm. As the authors of a 2016 Government Accountability Office Report note, although “[t]he agencies may . . . withhold approval of the mine based on the findings of the environmental analysis. . .BLM and Forest Service officials told us that they were not aware of any instances where this had occurred.”

In cases where the General Mining Law directly applies, the USFS and other agencies have stated in official documents that they don’t have the authority to say no to mining if all other requirements can be satisfied.

It’s worth noting the loopholes in other environmental laws and policies that help enable irresponsible hardrock mining projects, including specific exemptions for mining within sections of the Clean Water Act.

Given all this, and since the BLM and USFS have only rarely exercised their discretion (when they have it) to deem a mine inappropriate, one of the only ways to protect specific federal lands from mining is with a mineral withdrawal–a federal land management tool which essentially disallows mining as a land use in a set boundary in order to maintain other public values in that designated area. A mineral withdrawal lasting for a 20 year period can be executed administratively through the executive branch, but a mineral withdrawal enacted in Congress is harder to reverse and has no expiration date.

CFC is currently working on securing a legislative mineral withdrawal for the Green River Valley bordering the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, to permanently protect it from the threat of an open-pit mine.

NEEDED REFORMS

Given all of these known problems and the colonial history of laws regulating hardrock mining on lands managed by the Federal Government, CFC supports reforms that would ensure mining is done responsibly, sustainably, and with the consent and involvement of the affected communities–especially Indigenous ones.

Momentum is building, but reform efforts for hardrock mining have been underway for decades. CFC agrees with many of the suggested reforms including efforts to: close loopholes for mining that currently exist in environmental laws like the aforementioned Clean Water Act; ensure Tribes and local communities have a robust say in the planning of mining operations; create a reliable fund for the cleanup of abandoned mines; give land use managers the ability to say “no” and encourage them to do so in response to mining when other competing land uses and values deem a mine inappropriate in a particular area.

Towards that goal, we’ve been supporting several efforts to achieve these important reforms including signing on to express our support for bills in Congress such as the Clean Energy Minerals Reform Act of 2022. We’re also engaging with the administration in the Interagency Working Group on Mining Regulations, Laws, and Permitting. This process is being undertaken by the administration to identify regulatory and congressional actions needed to update our hardrock mining regulatory structure to meet the principles for reform set out by the Whitehouse.

TAKE ACTION

It’s long past time to rethink how we approach hardrock mining. As we move beyond a fossil fuel economy, we may come to rely on materials provided by hardrock mines even more than we already do. We will have to meet these needs while also protecting communities and our environment.

Mining reform is needed now because our current system is setting us up to fail to achieve that goal. It’s going to take a lot of feedback and grassroots work to get the needed reforms over the finish line. Here are a few ways you can help.

First, use existing systems to secure a mineral withdrawal for the Green River Valley. Learn more here.

Next, submit your own comments to the Interagency Working Group. They are accepting public input through July 31st, 2022.

When you submit comments to the Interagency Working Group, please include some of the talking points here. Ask the Working Group to:

- Recommend a legislative withdrawal for the Green River Valley in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest and ask them to execute an administrative legislative withdrawal as well.

- Close loopholes for mining in environmental laws like the Clean Water Act.

- Add royalty payments for hardrock mines to help ensure cleanup of mines when all the extraction is done.

- Ensure strong environmental protections for all hardrock mining operations.

- Allow land managers to have discretion to decide where other resource values outweigh mining in particular areas.

- Create strong public participation, Tribal consultation, and community involvement processes in mining proposals on all Federal lands.

- Ensure responsible and thorough cleanup of abandoned mines.

- Create and fund an abandoned mine program to ensure government agencies have the resources they need to clean up all abandoned mines.

To comment either email comments to this address (miningreform@ios.doi.gov) or submit directly to the Federal Register here.

¹ Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970