The laws and guidelines regulating the way public lands are managed have come a long way, but the challenges we face today require an updated approach.

The Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP) was implemented almost thirty years ago. The plan–a series of federal policies and guidelines governing land uses within federally managed areas of the Pacific Northwest–was adopted at the height of the confrontation between environmentalists and the timber industry around over-harvesting practices that decimated old-growth forests in the 1980s and early 90s. The plan was shaped by hundreds of scientists from a wide range of fields of expertise. It was designed for the purpose of preserving the health of entire ecosystems, including the people that rely on our forests, rather than focusing solely on the preservation of individual threatened or endangered species.

The NWFP was an important and ground-breaking piece of federal policy. When it was adopted in 1994, it created new guidelines for federal agencies and fundamentally changed the nation’s approach to resource management on public land for the better. But when the policy was adopted, our understanding of climate change was just beginning to emerge and was not yet a factor in shaping policy decisions.

Now, scientists, policymakers, and the public all have a better understanding of the urgent need to slow and mitigate climate impacts, as well as the role that forests in the Pacific Northwest play in capturing carbon and slowing global climate change. In light of these factors, CFC and many leading scientists believe our national forest land management policies could use some updating.

HOW ARE FEDERAL LANDS CURRENTLY MANAGED?

Part of the way the Northwest Forest Plan set new guidelines for resource management was the creation of several different land allocation designations that set management objectives for specific areas. The goal was to balance competing land use objectives and to protect the long-term health of forests, wildlife, and waterways.

Since the NWFP was adopted, timber harvests have mainly been proposed and discussed in areas within four of these designations:

Late-Successional Reserves (LSR)

Late-Successional Reserves are areas set aside to support or advance old-growth characteristics. It should be noted that this old-growth-focused management objective still allows some logging (mostly thinning) and this has been a source of conflict and disagreement through the years.

Riparian Reserves

Riparian Reserves

Under the NWFP, forest management in Riparian Reserves (habitat areas near streams and rivers) is supposed to support riparian health, but how one interprets this goal varies and management can also include thinning.

Adaptive Management Areas

Adaptive Management Areas

Compared to other designations, Adaptive Management Areas are smaller and intended to allow the US Forest Service a degree of experimentation with management interpretations. These are places where the impacts of restoration and harvest techniques are tested, implemented, and measured. But, of late, we have seen a rise in fairly intensive logging projects in these areas, mostly under the stated goal of bringing back huckleberry picking areas.

Matrix

Matrix

Matrix lands were intended to meet multiple objectives within the landscape, including the production of commercial yields of wood, diversification of habitat areas, and corridors between dispersed mature and old-growth habitat areas. The vast majority of timber harvest in national forests occurs on Matrix land. Unfortunately, that has led some to misinterpret the management objective of Matrix lands as places solely intended for free-for-all timber production.

RETHINKING THE MATRIX

In our Climate Resilience Guidebook, published in 2017, we outlined land management recommendations and restoration strategies that can be implemented at the local level to build resilience and limit the impacts of climate change. The Guidebook looked into how the different designations created by the NWFP relate to the conservation of species and habitats.

As we prepare to publish a new edition of the Guidebook, we are digging deeper into the role of these designations, especially that of Matrix lands. It’s vital to do that work now. The NWFP will be undergoing a long-anticipated update in the coming years, and scientists and conservationists will have opportunities to influence the new guidelines and objectives. We are interested in exploring how our knowledge of climate change and carbon sequestration may influence how we, collectively, may want to view the role of Matrix lands in national forests.

As we prepare to publish a new edition of the Guidebook, we are digging deeper into the role of these designations, especially that of Matrix lands. It’s vital to do that work now. The NWFP will be undergoing a long-anticipated update in the coming years, and scientists and conservationists will have opportunities to influence the new guidelines and objectives. We are interested in exploring how our knowledge of climate change and carbon sequestration may influence how we, collectively, may want to view the role of Matrix lands in national forests.

There are many questions that require investigation. Is it time for management conversations to more directly consider how carbon sequestration in Matrix lands can influence future climate impacts? Since drought and fires impact the entire forest, do we need to update our thinking about the management goals of Matrix lands to include their potential value as habitat refugia (important places where plant or animal populations can survive periods of unfavorable conditions), even if these Matrix lands make imperfect substitutes for areas designated as LSRs or Wilderness?

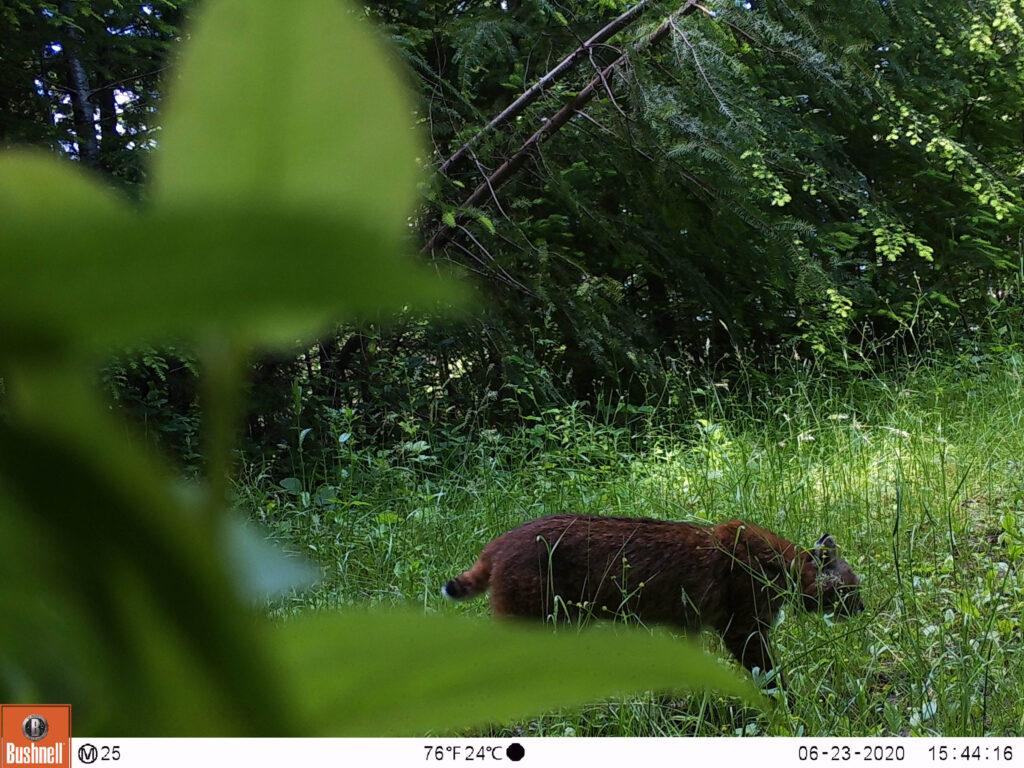

A selection of images from CFC’s wildlife cameras taken on Matrix lands

The new edition of the Guidebook will help elucidate answers to these questions and more. It will do so by synthesizing our knowledge from on-the-ground experience, insights from the latest scientific research, and data from mapping layers. All of this will allow CFC to gain a better idea of what changes to the Northwest Forest Plan may be needed to sustainably manage public resources while preserving ecosystem health and biodiversity in a changing world.

Locally, the insights we gain will impact our recommendations and priorities related to our work discussing and negotiating timber sales in forest collaboratives and our work, generally, with federal and state agencies. We will also use these insights to influence the Gifford Pinchot National Forest Plan and the Mount St. Helens Comprehensive Management Plan, two federal planning documents that will be updated after the NWFP and that will both be critically important to how our local federal lands are managed well into the future.

It’s time to revisit how we think about Matrix lands. We aim to publish a set of recommendations for this revision process and an outline of strategies we can all push forward through the various levels of conversation and public involvement, from the individual on up to the national stage.